Waterworld

Leaving the coast, again, after a week long kayak camping trip with friends in the Broughton Archipelago. It’s a foggy, soggy waterworld of giant trees, humpback whales, orca, and forests of bull kelp. Anyone who’s paddled these ocean waters knows it’s a fine mix of mystery, misery, and magic. (It’s never an adventure without a little adversity.) And I am relieved, as always, that places like this still exist.

It’s my third trip into these waters, located off the northern end of Vancouver Island, where the Salish Sea reaches for the Pacific. The area is the traditional territory of the Musgamagw Dzawada'enuxw, Namgis, Ma'amtagila and Tlowitsis nations of the Kwakwaka'wakw peoples. You can see evidence of thousands of years of habitation on almost every island; shell middens, culturally modified trees, sculptured clam beds, and narrow canoe runs cleared of rocks by ancient hands.

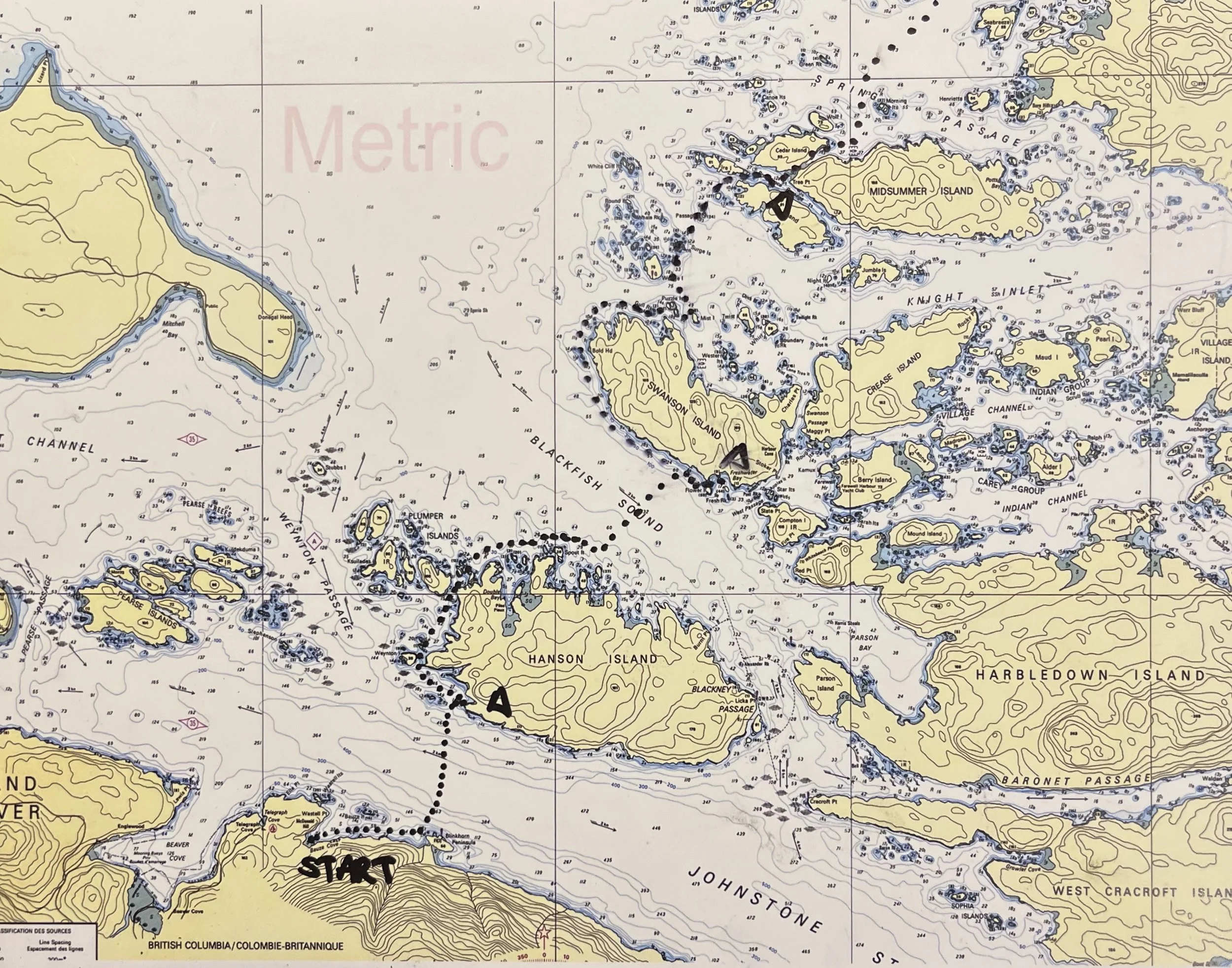

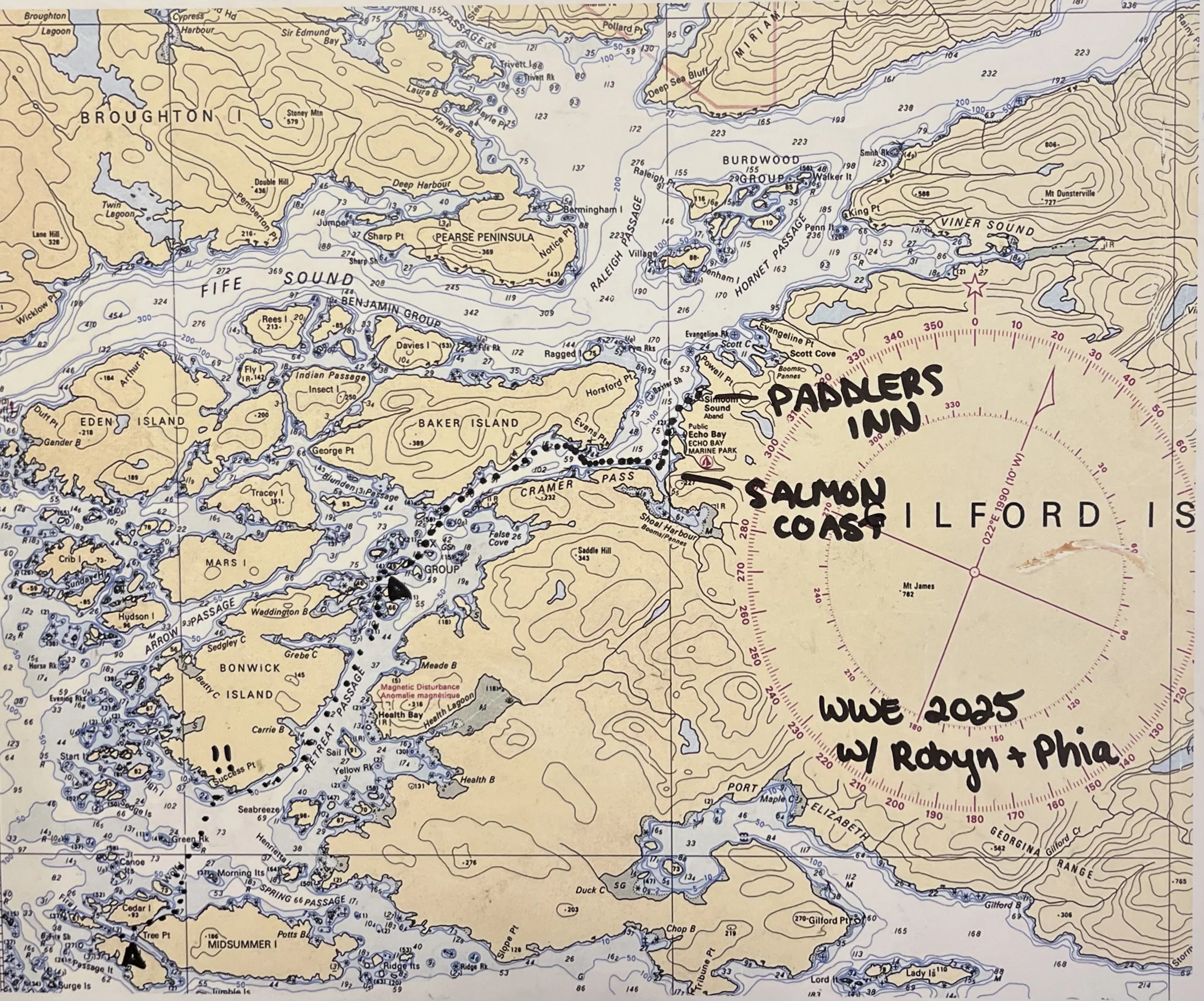

To get there you have to paddle across Johnstone Strait, and then Blackfish Sound, a harrowing experience in pea soup fog with only a deck mounted compass to guide our way. Luckily we had two professional guides with us, courtesy of local outfitters Spirit of the West Adventures. Both Robyn and Phia, badass and immensely capable young women, exude confidence. Each crossing is a trust exercise, but successfully navigated. There is palpable relief when a ghostly wall of cedars once again appear out of the mist.

The main attraction here is what some euphemistically call “charismatic megafauna”; a quaint way to say larger than life creatures are everywhere. A curious sea lion surprises our crew, baring its teeth before barking in disdain and slipping back beneath the surface. Huge lion’s mane jelly fish slip against our hull, stinging tentacles trailing behind, tasting the blades of our paddles. A humpback surfaces without warning twenty metres in front of our boats, eliciting gasps of surprise. And in the evening, the black sail of a male orca cuts between islands in front of our campsite. At nightfall, we hear the cetaceans breath and blow, as we lie in our tents. When they breach, it sounds like a gunshot. Even exhausted, it is hard to sleep.

One night is spent on Hanson Island, and as I lift clumsily out of my kayak cockpit I am reminded that this is the home of Orca Lab, and Paul Spong. A decade ago I first heard of his quixotic pursuit to not only dedicate his life to understanding the complex family relationships of the ocean’s most powerful predator, but also to try and right what he believes to be a terrible wrong.

Spong wants to create a retirement home, of sorts, for captured orca. One in particular, Corky at San Diego’s SeaWorld, has been the focus of his ongoing intense efforts. Captured in British Columbia in 1969, Corky is the longest-held captive orca in the world, and the last surviving Northern Resident orca in captivity.

I was so moved by his efforts that in 2018 I brought his story to a national radio audience when I was guest hosting on CBC’s The Sunday Edition. Here is that interview, for those who want to hear the story in his words. Below, some pictures of this summer’s latest trip. And in case you were wondering? Yes, I will someday go back.